Arkansas Studies Mini-Reactor Recycling of Nuclear Waste 2023

An informal coalition of Arkansas political, utility, and academic leaders is considering nuclear green energy.

Act 259, sponsored by Jonesboro state Rep. Jack Ladyman, requires the state to study the technical and economic feasibility of recycling spent nuclear fuel rods.

Conventional nuclear reactors like Arkansas Nuclear One on Lake Dardanelle would supply those rods. If successful, the recycling would use a tested but underutilized technology to manufacture fuel for miniature nuclear reactors whose zero-emissions electricity might save the globe.

Ladyman’s group comprises Arkansas Electric Cooperatives Corp. CEO Buddy Hasten, University of Arkansas System President Donald R. Bobbitt, and Texarkana’s John Warmack, partner at Warmack and Co. LLC., his family’s lengthy real estate development enterprise.

Warmack, an engineer, has worked for years to change energy policy to recycle used nuclear rods. On Tuesday, he told Arkansas Business that if economics work, liquid sodium fast reactors may power homes and businesses.

“This Arkansas study will model what we intend to do and issue an economic report to prove up or disprove the economics of recycling moving forward,” Warmack said. “Its main goal is to show recycling’s real economics.”

Recycled fuel won’t power Arkansas mini-nuclear reactors anytime soon. The technique has potential, but testing and development will take years.

Last month, Nucor Corp., which has steel mills in Mississippi County and nationwide, signed a memorandum of understanding with Portland, Oregon-based NuScale Power Corp. to explore using small modular nuclear reactors to provide baseload electricity to its electric arc furnace mills. Arkansas has one.

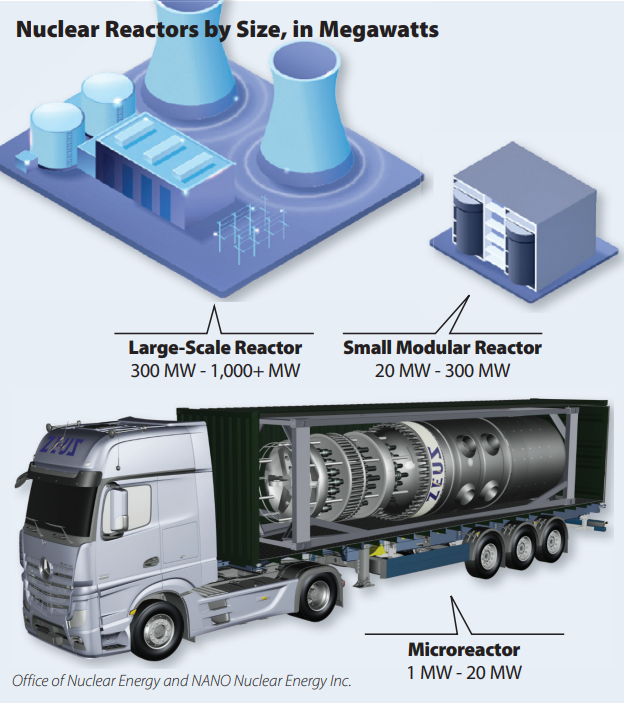

New York-based NANO Nuclear Energy Inc. is developing tractor-trailer-sized micro-nuclear power reactors. The Idaho National Laboratory has approved the science underpinning the Arkansas recycling project, so the business will start making nuclear fuel there.

“Obviously, we need a baseload energy source to replace coal,” Ladyman said in a recent phone conversation. “Nuclear is emission-free, and nobody’s doing what we’re doing. Science exists, but commercial viability is unknown. Arkansas will lead if we can do this.

“The University of Arkansas would have experts and graduates who have monitored the process, and we’ll have companies like GE or Siemens or Pratt & Whitney coming in to build generators if they see this is a viable business to get into.

Modular plants are factory-built. Ladyman, an engineer, said they’re smaller and not multibillion-dollar facilities like the old nuclear.

It’s nuclear power’s future.

Rods stored

Warmack said inflated building costs and cost overruns destroyed practically all new planning for huge classical nuclear facilities years ago, but technology and economics now favor small reactors that can power 20,000 homes.

Nevada and New Mexico have opposed proposals to store used nuclear fuel rods, although Ladyman’s recycling technique would be distinct from importing and storing nuclear material.

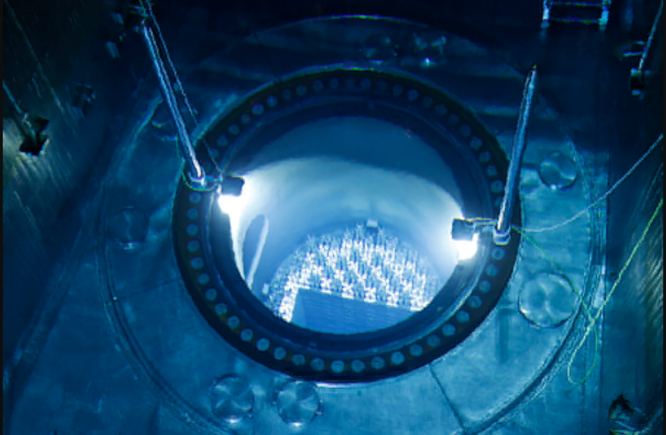

Arkansas Nuclear One’s two reactor units generate and store spent fuel rods. The plant’s last refueling occurred in April, and as per business tradition for over 50 years, the spent rods were originally deposited into a storage pool to cool down. “The concrete and steel pool and the water shield workers from radioactivity,” said Mara M. Hartmann, a spokeswoman for Entergy Corp., the parent company of Entergy Arkansas, which gets 70% of its power from ANO and the Grand Gulf nuclear reactor in Mississippi.

Hartmann told Arkansas Business that spent rods are housed in dry castings, “large steel-reinforced concrete containers,” once they cool. These casks are for long-term storage until a permanent disposal location is found. She stated the containers are earthquake-, storm-, and fire-resistant. “ANO has 100 dry fuel storage casks that are safe to touch.”

Since typical reactors consume just 5% of reactive material, spent rods retain much of their energy. The rods are radioactive for thousands of years, and the US has no permanent disposal site since a plan for a countrywide disposal plant deep under Yucca Mountain in Nevada met political opposition.

If Ladyman’s method works, the recycling factory may accept spent rods from ANO and around 50 additional nuclear stations nationwide.

Warmack said Manhattan Project veterans committed to postwar peaceful nuclear development provided the framework for Arkansas’s objectives. He claimed that President Bill Clinton shut down the promising technology for political reasons.

“In [circa] 1947-48 brainstorming sessions, Enrico Fermi, the daddy of the neutron process, proposed the liquid sodium fast reactor and recycling, and the government funded extensive research on pyroprocessing,” Warmack said of the Arkansas electrochemical recycling method. It was tested and debugged before commercial release. Warmack claimed the Clinton government terminated it in the 1990s, when nuclear energy was unpopular.

Warmack noted that pyroprocessing offers benefits over “PUREX” recycling, but it never recovered. PUREX separates uranium and plutonium using acid and solvent. Pyroprocessing turns the oxide components of spent nuclear rod pellets into metal. The metal is submerged in molten salt and treated to electric current to transform uranium into fuel for “fast reactors” in development.

Ladyman said no nuclear recycling site has been chosen, and even if the science proves affordable, establishing infrastructure and overcoming federal bureaucracy will take years. Act 259 requires the Arkansas Department of Energy & Environment to seek federal money for the recycling project from the Congressional Nuclear Waste Fund, a $45 billion fund established in the 1970s.

Ladyman stated a modest nuclear reactor would be near to a large recycling plant if recycling started.

Utility Vets

Arkansas Commerce Secretary Hugh McDonald told Arkansas Business that he hadn’t examined Act 259, but the country needs additional nuclear power.

“It has to be part of the mix going forward in providing reliable electricity around the clock,” the former Entergy Arkansas CEO stated.

I’ll wear my old Entergy cap. Arkansas Nuclear One and Grand Gulf, Mississippi—we held all of ANO but just part of Grand Gulf. Arkansas Entergy customers use 65%–70% nuclear electricity.

Hasten, CEO of Electric Cooperatives of Arkansas, strongly advocates small nuclear reactors as baseload energy. As a submarine officer, he ran tiny reactors deep beneath the North Pole.

The state’s 17 distribution cooperatives service 600,000 households and businesses with wholesale power from AECC.

Hasten anticipated a cooperative power mix with additional solar, a generation bridge combined-cycle natural gas plant, and a network of modest nuclear reactors last year.

Hasten commented, “I understand that plant better than this office.”

“If America wants to be serious about net zero carbon, we need something energy-dense. Gas and coal. It was wood before. The only emission-free option now is nuclear.”